![]()

LTD

BTOD

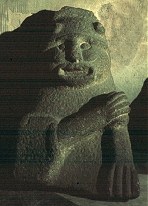

Detail of

Portrait of Tom Matthews

by Anthony Weir

Anthony Weir

IN MEMORIAM TOM MATTHEWS

1945 - 2003

The work of Nature is to

Undo the works of Man.

(Endless is the wilderness within.)

Stones are the souls of stars.

Stars are the souls of stone.

January 2004

|

We were both immediately attracted to each other. I saw Tom as a fellow non-joiner. I (always withdrawing rather than withdrawn) admired him for what I perceived to be his reclusivity and outsiderness: the 'guest in the guest room' of his poem . We were two 'Pessimysterians'. He regarded me, I thought, with amused and affectionate tolerance. He used to visit me for a weekend once every four or six weeks, and we discussed poetry, novels, music, politics, and so on. He would occasionally bring recordings of classical music for me to listen to and keep. In thirty years I don't think ever saw him stripped to the waist - let alone naked. His mind was kept even more wrapped up. People regarded him as a very 'private' person - though my word would be self-occlusive. I knew almost nothing about him, even by 2003 when, after taking early retirement from Ciments Lafarge (formerly Blue Circle Cement), we spent a week together in an old shepherd's house by the river Aveyron in France - my idea of heaven. I knew he had a brother in the charming town of Guelph (Ontario), a sister in Belfast, another sister in Exeter, and a friend called Pauline who lived nearby though I did not know that he had known her for fourteen years and was her closest friend. I knew that Pauline, like myself, was keen to move out of the claustrophobic, arrogant anglosphere of the United Kingdom, because Tom enthusiastically participated on her behalf when I went looking at a couple of houses for sale in Quercy. When I heard of his death from a massive heart attack while out running on New Year's Eve 2003, I was surprised. He had been a cross-country runner since his early teens. But his addiction to it in later years (despite a damaged knee) only further weakened a genetically-weak heart. Yet he thought that his portly brother-in-law (a doctor) would collapse before he did. As I said, I had thought Tom almost as reclusive and misanthropic as myself, if less joyous in food and music (especially Indian classical and Chopin), dogs, paintings, wine (and marc), trees, rugs, spiders, megaliths and improvisation - though perhaps he was more appreciative of contemporary poetry in English. But neighbours said that he was rarely at his home in Stoke-on-Trent - what with his friendships, a walking-group, stammerers' support groups, and other activities that he never mentioned to me. I learned that his collection of craft ceramics (which I started 25 years ago) possibly rivals my own. He compartmentalised his life and the people in his life, keeping his friends apart from each other, and his family from his friends. We had discussed old age, dying, death, disposal and wills when we were together in Quercy. I had offered him 'free space' in my Brocks' Acre thicket which is a badger-sanctuary and where I have permission to bury and be buried, so long as there is no permanent grave marker like those in churchyards and cemeteries. I had expressed to him my enthusiasm for the autonomy of suicide, reinforced by my horror of the medical bureaucracy which takes over the aged: part of my horror of doctors who seriously damaged my life, and made the last years of my mother and the last weeks of my aunt so helpless and degraded. After unpleasant experiences with local doctors, I de-registered some years ago, even before my mother was deprived of all dignity by being bundled into a hospital ward and dosed continually with antibiotics and other drugs - despite my protestations and her 'living will' asking to be left to die naturally and in peace. To rescue her from further degradation by the Funeral Parlour industry, I buried her myself, in a wicker coffin I had had specially made, collecting her from the morgue in my car and wrapping her in Irish damask tablecloths which had been stored at the bottom of a wooden chest. Tom had been one of hundreds of thousands who had seen the earlier cremation of her sister on BBC television (as part of a programme on "alternative" funerals, called THE END ), which I organised entirely myself -from cardboard coffin to collection of the ashes. Some ashes were buried under a beautiful stone and primroses at Brocks' Acre - where, on the way to the family grave close to where she was born, I stopped to add a lock of my mother's hair. Since these funerals I have enormous respect for mortuary-men and gravediggers. I had of course no idea that Tom would so soon himself be claimed by the Funeral Industry - though he successfully escaped the clutches of Medical-Pharmaceutical one and died as, I imagine he would have wanted: quickly and in the open air. But perhaps I am wrong, for his 'Belfast sister' intimated to me that Tom had written in his will that I could claim any of his thousands of books and CDs if I went to do so within three months of his death. Surely he should have known that I now would not want to be a vulture (though I greatly approve of the Zoroastrian/Parsi Towers of Silence which attract this horribly-declining species) ? That I (even though I once spent three months in jail for shoplifting groceries) would not want to rattle around his uncosy house with family and friends I would have nothing in common with and would never see again - just to acquire yet more goods in a society wherein even the poor are obscenely rich ? So, though Tom's "Belfast sister" asked me to cross the Irish Sea with her and her doctor-husband and claim what loot I wanted and was 'entitled' to, I decided that it (in the modern euphemistic jargon) would be 'inappropriate' for me to go. Even more inappropriate for me to stand up in the crematorium and read one or more of his very private, wry poems to an audience. I think that he deplored as much as I do the modern fashion for public poetry events - a branch of the entertainment and publishing industries that benefits only the most showy and shallow wordsmiths. The diffident but stubborn Tom I knew certainly would not have expected or even wanted me to join his other friends and family for his cremation - an outrageous idea. For me the truest tribute to the Tom I knew is to stay away from his funeral, both of us in separate spiritual guest room s. But was he the Tom I thought I knew, veiled, like my mother, in diffidence ? Am I the Anthony within his limited ken ? Though we were 'friends' for thirty years (and read each other's poetry - to some extent each other's only audience...) perhaps we did not know each other at all. I am an 'open book' to all, intimating my feelings and thoughts, and incapable of harbouring secrets. Tom was veiled, almost inscrutable, lurking invisibly behind a stammering - and charming - diffidence. If "old friends" do not know each other at all, friendship is only false connection or a substitute for elective affinity. Indeed in the last five years of his life Tom hardly communicated with me - even when I was arranging the trip to Quercy. Tom would certainly not have come to county Down if I, rather than he, had suddenly died. My mother's friends abandoned her entirely in her last years, because of her misdiagnosed 'dementia' (in fact Pressure Hydrocephalus ). And I excluded my cousin's wife from my aunt Marcella's funeral because she - to whose family Marcella had been very generous - abandoned my aunt entirely at the end, even though the hospital was only 2 kilometres away. When I jumped bail on the shoplifting charge, Tom harboured me in his house for a couple of weeks, where I planted trees and shrubs in his neglected garden before I returned home and eventually was collected by the police. (They had to rush me from the holding cell to hospital because I had taken several barbiturates in order to be 'taken dead rather than alive'. I think the romantic egregiousness in me appealed to Tom.) Tom knew that I gave away a sizeable portion of my mother's estate to a Donkey Sanctuary in county Cork; that I find the whole acquisition-and-disposal-of-property business very sordid. This is one of the ways that wealth is kept away from the poor. I would wish all Tom's CDs and books to be given to the local library service, and for all his other property (including two computers & two sound-systems) to be given to very small, struggling charities (for animal or tree protection, perhaps ?) of the kind that cannot produce glossy magazines. His sister told me that 'donation to a charity of my choice' would be preferable to flowers. Neither idea would have entered my head - especially as very little of Tom's tens of thousands of pounds was given to the poor or needy. They went into Investment in the summer of 2003. As for flowers: those at my aunt's and mother's funerals were from my shrubby garden whose floriferous and leafy winter sub-tropicality they both loved - its dry, poor, thin soil on porous rock enriched and watered by my urine and other 'waste'. ( Yucca gloriosa flowering in January; Beschorneria yuccoides in March.) My own sentiments about my own end very much echo those of Mr Henchard in Thomas Hardy's Mayor of Casterbridge - though for very different reasons. On reflection, perhaps Tom was not trying to manipulate me from beyond the grave, but challenging me, wondering if I would react as I have done... ...by declaring that I now understand that enigmatic and gnomic if not gnostic Biblical injunction by the disciple of Diogenes, Jesus of Galilee (Matthew VIII, 22): LET THE DEAD BURY THEIR OWN DEAD. Or perhaps the source of my angst has been nothing to do with Tom, but with the conflict between my own egregiousness au ban de la société , and the desires, fantasies and conventionality of the executors and other beneficiaries of his Will... 7th January 2004 |

|

8th January 2004

Dear Pauline

Unlike Tom's sister, you made it rather difficult for me to tell you that I did not want to attend Tom's funeral or claim any of his books and records.

You told me how much he admired me, how I was his best friend, how fitting it would be for me to read one or more of his poems at the Crematorium.

Bah! Humbug!

Today I received this letter from Messrs Bowcock & Pursaill, Solicitors, addressed to

Since I know that Tom's estate was worth at least £200,000, and he knew that I was just a few thousand euros short of the wherewithal to move permanently to Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val, this legacy announces exactly the esteem in which he held me as compared with his wealthy family and friends. My dog Oscar gives me more and deeper joy in one day than Tom was capable of - or wanted to - in 30 years. And, of course, is immeasurably more open and receptive. I shall not even reply to the solicitor's letter. Burn the paintings. Yours truly, "Disaffected of Downpatrick."

|

|

poems by Tom Matthews

|