|

|

PILLAR-STONES

OGAM STONES

& CROSS-PILLARS

There are many unique pictures on this page:

please be patient while they download.

"Cloghadda", Tamnaharry, county Down

_________________________

photographs and text by

Anthony Weir

_________________________

The landscape of Ireland (littered with so much else)

is also littered with uncounted Standing-stones (also known as Menhirs). Two thousand years ago there may have been ten times as many as there are today. Perhaps ten thousand now survive, ranging from less than one metre high to more than seven metres.

Ballygilbert, county Antrim: just over one metre high

Often they have a name like "Cloghmore" from the Irish for 'big stone'

(cloch mór),

or "Cloghadda", from the Irish for long - or broad -stone

(cloch fháda).

Click on the thumbnail for a larger picture

Sometimes their Irish name is translated and they are known as "The Long Stone".

The Long Stone, Forenaghts Great, county Kildare:

over 5 metres high

Cloghstuckagh, Moyvoughly, county Westmeath

"Cloghstuckagh" means 'prominent stone'.

Not all stones are ancient: some were erected in the 18th and 19th centuries as Scratching-posts for cattle. On the other hand, one in County Down which is touchingly held steady by a steel hawser wrapped round a tree marked a Bronze Age burial of burnt bones.

Carrownacaw, county Down

Some Irish menhirs seem to have been altered, as at Tamnaharry (above), or like the 'shouldered' stone at Barnmeen, county Down.

click on the thumbnail for a high-resolution photo

But others were obviously erected because of existing characteristics, subsequently enhanced by further weathering.

Ardristan, county Carlow

In some cases, weather has actually split the stone into two or more parts.

Graigue, county Kerry

Quartzite stones were selected for their perceived numinous quality, and quartzite pebbles are often to be found in association with prehistoric and pre-Norman monuments in Ireland.

Cregg, county Derry

Pairs of stones also occur, of which one may be pointed or rounded, and the other flattened or grooved, suggesting male and female. Cattle were driven between these to encourage fertility.

Boherboy, county Dublin

Saval More private burying-ground, county Down

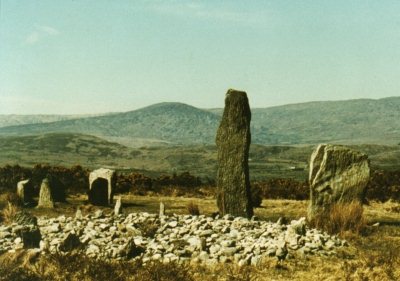

Alignments or Stone-rows are also numerous.

click on the picture for high-resolution photographs

Castlenalacht, county Cork

They are sometimes associated with

stone circles

.

![]() Beaghmore, county Tyrone

Beaghmore, county Tyrone

![]()

click on the pictures for more, high-resolution photographs

The stone circles associated with alignments are usually of small stones; at Beaghmore some are only a few centimetres high.

click on the picture for high-resolution photographs

Kealkil, county Cork

At Kealkil, as at Beaghmore, the alignment and circle are also accompanied by a circular low heap of stones.

Circles of tall stones, being sufficiently prominent, do not have associated alignments. But sometimes, as at Ardgroom Outward, they may have one or more outlier.

click on the picture for high-resolution photographs

Ardgroom Outward, county Cork - with outlier to right

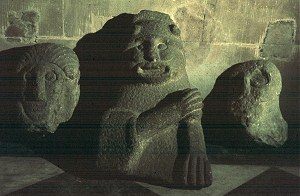

When ogam writing was introduced to Ireland from Wales, just before Christianity arrived, some long-standing stones were used for inscriptions which were mostly memorials of named people. The word 'ogam' is derived from Oigmiú, the smith-god who became the script-god. Another aspect of the smith-god is Nuadú of the silver arm (and horned helmet) whose statue (formerly in Armagh Cathedral) is the logo of this site.

He is shown holding his prosthesis. His maiming recalls that of Hephaistos, the smith-god of the Greeks.

Ogam, essentially notches, was admirably designed for carving by adze or axe on beams and large chunks of wood as well as by chisel or even axe on stone. The alphabet was designed in four groups of five letters, thus:

(V can also be read as F)

Detail of one of several stones at Dunloe, county Kerry

A typical inscription has the name of the person to be remembered, plus MAQI MUCOI ('son of the people of'), followed by the name of an ancestor or divinity.

Drumlohan, county Waterford

click on the picture to see another Waterford stone

Few are now entirely legible, due to weathering and other damage. The letters on the above stone have been enhanced by charcoal, which (unlike chalk) very quickly washes away.

As with standing-stones, an ogam-inscribed stone can be quite small. One, at Aghascrebagh in county Tyrone is only 1.5 metres high,

Lugnagappul, county Kerry

while three in the Field of Blood (Parc na Foladh) at Lugnagappul on the Dingle Peninsula, are less than one metre high. As with standing-stones and other prehistoric monuments, white quartzite pebbles are at their base.

Following the uniquely peaceful Christianisation of Ireland, it was not long before Christian crosses appeared on ogam stones. The Dingle Penininsula has dozens of cross-pillars and cross-inscribed ogam stones, of all shapes and sizes.

Ballinvoher, county Kerry

Ballintaggart, county Kerry

Arraglen, county Kerry - with quartzite pebbles

Maumanorig, county Kerry

Cross-inscribed ogam stones are usually associated with Celtic monasteries which, before the Westernisation of the Coptic-inspired Irish church (which was not completed until long after the Normans were invited over), were run by hereditary abbots.

Ratass, county Kerry

Perforated, ogam-inscribed pillarstone,

with crude cross in front of 12th century church,

Kilmalkedar, county Kerry

At the great monastery of Clonmacnois one of the many gravestones or pillow-stones for deceased monks bears the name Colman in both ogam and modern characters.

Ogam faded out after the arrival of Christianity, and pillar-stones became more elaborately carved with cruciform and cycliform designs. These are discussed on the page entitled

![]() Cross-pillars and Cross-slabs

Cross-pillars and Cross-slabs

![]()

Kilfountan, county Kerry

|

|

Photos and text anti-copyright by

Anthony Weir, whose

EARLY IRELAND: A FIELD GUIDE

was published in 1980, quickly sold out,

and was never reprinted.

|