|

POETRY

post-millennium maggot

jewels and shit: poems by rimbaud villon's dialogue with his heart

vasko popa: a shepherd of

genrikh sapgir:

BETWEEN POETRY AND PROSE

ESSAYS a muezzin from the tower of darkness

satan in the groin

a holy dog and a dog-headed saint

field guide to megalithic ireland

The meaning of the word icon (ikon) has degenerated from the image of an admirable person to a symbol on a computer-screen. The word franchise in French signifies honesty - but in English denotes a commercial concession.

|

FOOLS FOR NOTHINGNESSThe atheist as failed saint:

Antonin Artaud, Jean Genet and

|

|

We live in a time - a European, imperial and North American time, a Promethean smash-and-grab-time, when holiness counts for less than nothing, and wealthy, vacuous celebrity is all that matters.

Mother Teresa wanted only to let people die comunally in rows. This was her rational understanding of grace, against which our vain culture of the pursuit of the happiness-chimæra is set.

The first true

Fool-for-Christ

seems to have been St. Andrew of Constantinople in the 9th century. The theology behind this interesting Christian Path is the achievement of perfect humility through ascetic "madness". The term comes from St Paul:

The first one in Russia was St. Prokopios of Ustjug who lived in the 13th century and was originally a German merchant who became a monk, and, later, a Fool for Christ . There were many such Yurodivyi in the 16th century - such as SS. John of Moscow, John-the-Hairy of Rostov, and Lavrentii of Kaluga. This peculiar form of asceticism, which owes much to Buddhist, Hindu and Sufi awarenesses, has continued until the present day. One of the famous latter-day saints was the 18th century Xenia of Petersburg. After her husband's death she dressed in his clothes and wandered the streets of St. Petersburg as a beggar. She had many prophetic visions. The last recognised one was St. Theoktista of Voronezh, who was martyred under Czar Stalin Djugashvili in 1936. There may well be more latter-day saints. The problem with renouncers like Xenia is, of course, that one has to have something to renounce. St Francis is another striking example. He was perhaps the West's only recorded Fool for Christ - and he escaped burning for heresy only so he could be incorporated into the trans-national control-machine of the Catholic church. The long moral vacuum of Europe (recently and hugely enlarged by the infantilism that comes from a culture of gratification of desire) can perhaps only be filled by an unlikely rational compromise between Holy Folly (Hindu, Buddhist, Sufi or Orthodox) and the kind of visionary artistic integrity of an Artaud or a Genet... But only the unnoticeable and unattached can be truly fearless and blameless. Today the weather is beautiful and I am busy learning to be nobody but a Fool for Nothingness with my dog. I am writing about two troubled French Fools for Nothingness, the hems of whose garments I would probably be fit to touch.

|

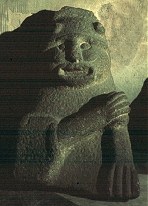

Saint Vassily of Moscow,

I am indebted to my friend Dr Sauli Siekkinen of Helsinki for his information on Russian saints.

• Further reading: Chekhov's short story "The Bet". |

Antonin Artaud and Jean Genet are two men who could have been holy saints if they had been born in a culture which had not trashed holiness and integrity. Furthermore, the pretensiousness that tends to afflict the visionary (in the same way as doctrine tends to corrupt the religious) seriously undermined them both. Perhaps the least-recognised evil of mind is to take itself (rather than life ) seriously. Genet was infected by the vainglory of being a littérateur, and even more by the unwholesome Sartre and his circle of pseudo-philosophers. Artaud became insane because of simply getting lost in the labyrinth of his thoughts: a Minotaur par excellence.

1. ANTONIN ARTAUD:

holy (in spite of himself) nihilist

On Antonin Artaud

by

Susan Sontag

In more direct metaphors, he rages against the chronic erosion of his ideas , the way his thought crumbles beneath him or leaks away; he describes his mind as fissured, deteriorating, petrifying, liquefying, coagulating, empty, impenetrably dense: words rot. Artaud suffers not from doubt as to whether his "I" thinks but from a conviction that he does not possess his own thought. He does not say that he is unable to think; he says that he does not "have" thoughtwhich he takes to be much more than having correct ideas or judgments.

"Having thought" means that process by which thought sustains itself, manifests itself to itself, and is answerable "to all the circumstances of feeling and of life." It is in this sense of thought, which treats thought as both subject and object of itself, that Artaud claims not to "have" it. Artaud shows how the Hegelian, dramatistic, self-regarding consciousness can reach the state of total alienation (instead of detached, comprehensive wisdom)because the mind remains an object.

The language that Artaud uses is profoundly contradictory. His imagery is materialistic (making the mind into a thing or object ), but his demand on the mind amounts to the purest philosophical idealism. He refuses to consider consciousness except as a process. Yet it is the process character of consciousnessits unseizability and fluxthat he experiences as hell. "The real pain," says Artaud, "is to feel one's thought shift within oneself."

The consequence of Artaud's verdict upon himselfhis conviction of his chronic alienation from his own consciousnessis that his mental deficit becomes, directly or indirectly, the dominant, inexhaustible subject of his writings. Some of Artaud's accounts of his Passion of thought are almost too painful to read. He elaborates little on his emotionspanic, confusion, rage, dread. His gift was not for psychological understanding (which, not being good at it, he dismissed as trivial) but for a more original mode of description, a kind of physiological phenomenology of his unending desolation. Artaud's claim in The Nerve Meter that no one has ever so accurately charted his "intimate" self is not an exaggeration. Nowhere in the entire history of writing in the first person is there as tireless and detailed a record of the microstructure of mental pain.

The quality of one's consciousness is Artaud's final standard. thus, his intellectual distress is at the same time the most acute physical distress, and each statement about his body. Indeed, what causes his incurable pain of consciousness is precisely his refusal to consider the mind apart from the situation of the flesh.

The difficulties that Artaud laments persist because he is thinking about the unthinkableabout how body is mind and how mind is also a body. This inexhaustible paradox is mirrored in Artaud's wish to produce art that is at the same time anti-art. The latter paradox, however, is more hypothetical than real. Ignoring Artaud's disclaimers, readers will inevitably assimilate his strategies of discourse to art whenever those strategies reach (as they often do ) a certain triumphant pitch of incandescence.

Artaud's work denies that there is any difference between art and thought, between poetry and truth. Despite the breaks in exposition and the varying of "forms" within each work, everything he wrote advances a line of argument. Artaud is always didactic. He never ceased insulting, complaining, exhorting, denouncingeven in the poetry written after he emerged from the insane asylum in Rodez, in 1946, in which language becomes partly unintelligible; that is, an unmediated physical presence. All his writing is in the first person, and is a mode of address in the mixed voices of incantation and discursive explanation. His activities are simultaneously art and reflections on art. In an early essay on painting, Artaud declares that works of art "are worth only as much as the conceptions on which they are founded " .

Artaud's criterion of spectacle is sensory violence, not sensory enchantment; beauty is a notion he never entertains. The experience of his work remains profoundly private. Artaud is someone who has made a spiritual trip for usa shaman. It would be presumptuous to reduce the geography of Artaud's trip to what can be colonized. Its authority lies in the parts that yield nothing for the reader except intense discomfort of the imagination.

Artaud's work becomes usable according to our needs, but the work vanishes behind our use of it. When we tire of using Artaud, we can return to his writings.

"Inspiration in stages,"

he says.

"One mustn't let in too much literature."

All art that expresses a radical discontent and aims at shattering complacencies of feeling risks being disarmed, neutralized, drained of its power to disturbby being admired, by being ( or seeming to be) too well understood, by becoming relevant. Most of the once exotic themes of Artaud's work have since become loudly topical: the wisdom (or lack of it) to be found in drugs, Oriental religions, magic, the life of North American Indians, body language, the insanity trip; the revolt against "literature," and the belligerent prestige of non-verbal arts; the appreciation of schizophrenia; the use of art as violence against the audience; the necessity for

obscenity.

Both in his work and in his life Artaud failed.

[As he had to if, unlike the surrealists, Picasso and his followers, he was to retain his integrity. For him, as for me, 'success' would have been the most pathetic failure. - A.W. ]

His work includes verse; prose poems; film scripts; writings on cinema, painting, and literature; essays, diatribes, and polemics on the theater; several plays, and notes for many unrealized theater projects, among them an opera; a historical novel; a four-part dramatic monologue written for radio; essays on the peyote cult of the Tarahumara Indians; radiant appearances in two great films (Gance's

Napoleon

and Dreyer's

The Passion of Joan of Arc

) and many minor ones; and hundreds of letters, his most accomplished "dramatic" formall of which amount to a broken, self-mutilated corpus, a vast collection of fragments. What he bequeathed was not achieved works of art but a singular presence, a poetics, an æsthetics of thought, a theology of culture, and a phenomenology of suffering.

Artaud in the nineteen-twenties had just about every taste (except enthusiasms for comic-books, science fiction, and Marxism ) that was to become prominent in the American counter-culture of the nineteen-sixties; and what he was reading in that decadethe Tibetan "Book of the Dead" [

properly:

Book of Living and Dying - A.W.]

, books on mysticism, psychiatry, anthropology, tarot, astrology, Yoga, acupunctureis like a prophetic anthology of the literature that has recently surfaced as popular reading among the advanced young."

[But Artaud's interest was not superficial or self-obsessed. - A.W.]

Artaud's Last Work

by

Maria Levitsky

Madman/theorist/philosopher/playwright Antonin Artaud's final work was a radiophonic creation entitled

"To Have Done With The Judgment Of God."

It was written after several years' internment in psychiatric institutions which roughly corresponded to the duration of World War II. During his stay at the asylum, Artaud's behavior was characterised by delusions, auditory hallucinations, glossolalia and violent tantrums. He underwent a myriad of bizarre treatments for this behavior including coma-inducing insulin therapy and electroshock therapy.

"Pour En Finir Avec le Judgement de Dieu"

is a heretic's scatalogical tirade at the extreme of the linguistic lunatic fringe. It was perhaps Artaud's electronic revenge against his incarcerators - an invective broadcast from the end of the mind.

It was commissioned in 1947 by Ferdinand Pouey, the director of dramatic and literary broadcasts for French Radio. The work defies description, and although it was actually recorded in the studios of the French Radio at the end of 1947 and scheduled to be broadcast at 10:45 PM on February 2, 1948, the broadcast was cancelled at the last minute by the director of French Radio, Vladimir Porche. Citing Artaud's scatalogical, vicious and obscene anti-American and anti-Catholic pronouncements as something that the French radio audience could do without, he upheld this censorship in the face of widespread support from many culturally prominent figures including Jean Cocteau, Jean Louis Barrault, René Clair and Paul Eluard. Pouey actually quit his job in protest. Artaud died a little over a month later, profoundly disappointed over the rejection of the work. It was not broadcast over the airwaves until thirty years later.

In the actual text of "To Have Done With The Judgment Of God" America is denounced as a baby factory war-mongering machine. Bloody and apocalyptic death rituals are described. Shit is vividly exalted as evidence of life and mortality. Questions about consciousness and knowledge are pursued and answered with more unanswerable questions. It all dead-ends in a scene in which God itself turns up on an autopsy table as a dissected organ taken from the defective corpse of mankind. In the recording all this would have been interspersed with shrieks, screams, grunts, and an extensive vocabulary of nonsense words - a glossolalia of word-like sounds invented by Artaud to give utterance to the dissociation of meaning from language.

One would be hard pressed to find anything like Artaud's work being broadcast on radio or TV now, but to get an approximation of an idea of it, do this: turn on the radio to any station [except BBC radios 3 or 4, of course] , turn on the TV with the sound up and the picture off, smoke a joint and just listen to the glorious sound of the babbling media. As good as electroshock therapy.

The information for this article was lifted directly from Alan Wiess' chapter entitled "Radio, Death and the Devil" in

The Wireless Imagination: Sound Radio and the Avant Garde,

edited by D. Kahn and G. Whitehead.

SIX QUOTATIONS

from Antonin Artaud

.

1. So long as we have failed to eliminate any of the causes of human despair, we do not have the right to try to eliminate those means by which man tries to cleanse himself of despair.

2. And what is an authentic madman? It is a man who preferred to become mad, in the socially accepted sense of the word, rather than forfeit a certain superior idea of human honor. So society has strangled in its asylums all those it wanted to get rid of or protect itself from, because they refused to become its accomplices in certain great nastinesses. For a madman is also a man whom society did not want to hear and whom it wanted to prevent from uttering certain intolerable truths.

3. I myself spent nine years in an insane asylum and I never had the obsession of suicide, but I know that each conversation with a psychiatrist, every morning at the time of his visit, made me want to hang myself, realizing that I would not be able to cut his throat.

You are outside life, you are above life, you have miseries which the ordinary man does not know, you exceed the normal level, and it is for this that men refuse to forgive you, you poison their peace of mind, you undermine their stability. You have irrepressible pains whose essence is to be inadaptable to any known state, indescribable in words. You have repeated and shifting pains, incurable pains, pains beyond imagining, pains which are neither of the body nor of the soul, but which partake of both. And I share your suffering, and I ask you: who dares to ration our relief? . . . We are not going to kill ourselves just yet. In the meantime, leave us the hell alone.

4. Destroy yourselves, you who are desperate, and you who are tortured in body and soul, abandon all hope. There is no more solace for you in this world. The world lives off your rotting flesh.

5. It is almost impossible to be a doctor and an honest man, but it is obscenely impossible to be a psychiatrist without at the same time bearing the stamp of the most incontestable madness: that of being unable to resist that old atavistic reflex of the mass of humanity, which makes any man of science who is absorbed by this mass a kind of natural and inborn enemy of all genius.

6. I abandoned the stage because I realised that the only colloquy I could have with an audience was to pull bombs out of my pockets and hurl them...

2. JEAN GENET:

ultra-sane criminal and dissident for whom everything cosy was false

(from an official French Jean Genet website)

Enfant de l'Assistance publique, Jean Genet est entré très jeune dans la délinquance, et a connu la colonie pénitentiaire de Mettray à la suite des délits mineurs qu'il avait pu commettre. Il s'engage à 18 ans dans la légion étrangère pour quitter la colonie, déserte en 1936, vagabonde dans toute l'Europe.

En 1942 il écrit son premier texte, alors qu'il se trouve en prison à Fresnes: Le condamné à mort, poème en alexandrins , et le fait imprimer à ses frais. Cocteau le soutient, après avoir lu les manuscrits de Notre-Dame des Fleurs (publié en 1944) et de Miracle de la rose (1946), et obtient pour lui une remise de peine. Il est libéré en mars 1944, et définitivement gracié en 1949.

En moins de trois ans il écrit

Le Journal d'un voleur, Querelle de Brest,

Pompes funèbres.

Il écrit aussi pour le théâtre :

Le Balcon

(1956),

Les Nègres

(1958) et

Les Paravents

(1961). Ses pièces le placent très vite au premier rang du répertoire contemporain.

En 1964, à l'annonce du suicide de son ami Abdallah, il prend la décision de renoncer à la littérature. Il entreprend un long voyage jusqu'en Extrême-Orient, et revient en France juste au moment des évènements de mai 1968. Il publie alors son premier article politique, en hommage à Cohn-Bendit.

La dernière partie de sa vie, il la consacre à l'engagement politique aux côtés des Black Panthers, puis des combattants palestiniens. En 1982, il se trouve à Beyrouth lors du massacre des camps de Sabra et de Chatila. Il reprend alors la plume pour rédiger Quatre heures à Chatila, l'un de ses textes les plus engagés. De 1983 à 1985 il rassemble des notes sur les noirs américains et les palestiniens, et sur leurs conditions d'emprisonnement.

En novembre 1985 il confie enfin le manuscrit d' Un Captif amoureux à son éditeur.

(adapted from other literary websites)

Jean Genet, the illegitimate son of a Parisian prostitute, was born on October 19, 1910, and orphaned seven months later. At the age of ten he was accused of theft. Although innocent of the charge, having been described as a thief, the young boy resolved to be a thief. "Thus," wrote Genet, "I decisively repudiated a world that had repudiated me."

At the age of thirteen, after having subsisted as a ward of the state, he inaugurated a life of crime and adventure by gaily spending, at a local fair in the Morvan, northern Auvergne where he had been fostered, a sum of money that his guardian had entrusted to him. From ages 15 to 18, Genet spent an impressionable period at the Mettray penitentiary, a place of hard labor, where a code of love, honor, gesture and justice was enforced by the inmates; and where his sexual awakening occurred. After this, serving in the French Foreign Legion, he went to Syria. This period was succeeded, upon desertion of the Legion, by travel to the Far East and numerous imprisonments, during which time he survived by petty theft, begging, and homosexual prostitution.

Between 1930 and 1940, he wandered through various European countries, living as a thief and male prostitute. At the age of 23, Genet was living in Spain, sleeping with a one-armed pimp, lice-ridden and begging - a period which became the basis for The Thief's Journal. Eventually, he found himself in Hitler's Germany where he felt strangely out of place. "I had a feeling of being in a camp of organized bandits. This is a nation of thieves, I felt. If I steal here, I accomplish no special act that could help me to realize myself. I merely obey the habitual order of things. I do not destroy it." So Genet hastened back to a country that for a time still obeyed the conventional moral code - a code in which the policeman and the criminal, right and wrong, are like Aristophanes' arrogant, achieving 'original people' cut in two by Zeus and placed in opposition to each other.

In 1942, after being imprisoned for theft, Genet began writing. His first effort was a poem in alexandrines called The Man Condemned to Death. He then turned to drama. Ignoring traditional plot and bourgeois psychology, Genet's plays rely heavily on ritual, transformation, illusion and interchangeable identities. His experiences in prison would inform much of his work. The homosexuals, prostitutes, thiefs and outcasts of his plays are trapped in self-destructive circles. They express the despair and loneliness of a man caught in a maze of mirrors, trapped by an endless progression of images that are, in reality, merely his own distorted reflection.

Genet's first dramatic effort was a poignant examination of the oppressed and the oppressor. In Deathwatch he experimented with a murderer in the role of hero. The play revolves around three inmates who struggle for domination of a prison cell while an unseen fourth prisoner watches on.

In his next play, The Maids, Genet portrayed the empowering ritual of two maids who take turns acting as "Madame," abusing each other as either servant or employer. The ceremony revealed not only the maids' hatred of the Madame's authority, but also their hatred of themselves for participating in the hierarchy that oppresses them.

In 1947, following his tenth conviction for theft, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. But his growing literary reputation induced a group of leading French authors (notably Sartre and Cocteau) to petition for his pardon, which was granted in 1948 by the president of France. As result, Genet's life changed radically and he became more writer than criminal. But he was naturally so addicted to theft that he stole diamonds from his hostesses at a literary reception. Sartre referred to him as holy and a saint.

His greatest drama was, ironically, first staged at a private club in London because it was considered too scandalous for Paris audiences. The Balcony is set in a grand and glorious brothel "of noble dimensions," a palace of illusions in which men can indulge their secret fantasies, perhaps as a judge inflicting punishment on a beautiful young thief, or as a dying Foreign Legionnaire being succoured (or, rather, sucked) by a beautiful Arab maiden. But outside the brothel, the country is caught up in a revolution, and the 'false' brothel-rôles become 'true' ones: the man who dressed up as a judge becomes a judge, the man who indulged his fantasy as a bishop becomes a bishop, and the man who desperately pretended to be a general becomes a general. We are all only rôles - and rôles are our importance.

In The Blacks, a troupe of colored actors enacts before a jury of white-masked blacks the ritualistic murder of a white of which they have been accused. The last of Genet's plays to be produced during his lifetime, The Screens, is his comment on the Algerian revolution. Like all of Genet's works, these plays are grotesque, sometimes bewildering, savage, and haunting. Simultaneously cultivating and denouncing the stage illusion, they exude a strange ritualistic, incantatory quality that successfully transforms life into a series of ceremonies and rituals that bring stability to an otherwise unbearable existence.

In addition to his plays and his Journal, Genet wrote several novels ( Our Lady of the Flowers, Miracle of the Rose, Querelle) and film scripts. Fassbinder made a famously balletic film of Querelle . Genet himself made a short silent picture about solitary prisoners masturbating - Un Chant D'Amour (1949). He died in Paris on April 15th, 1986.

NINE QUOTATIONS

from Jean Genet

1. Those who have not experienced the ecstasy of betrayal know nothing at all about ecstasy.

2. Repudiating the virtues of your world, criminals hopelessly agree to organize a forbidden universe. They agree to live in it. The air there is nauseating: they can breathe it.

Would Hamlet have felt the delicious fascination of suicide if he hadn't had an audience, and lines to speak?

3. When the judge calls the criminal's name out he stands up, and they are immediately linked by a strange biology that makes them both opposite and complementary. The one cannot exist without the other. Which is the sun and which is the shadow? It's well known some criminals have been great men.

4. I'm homosexual... How and why are idle questions - like wanting to know why my eyes are green.

5. I recognize in thieves, traitors and murderers, in the ruthless and the cunning, a deep beauty - a sunken beauty.

6. The fame of the famous owes little to their achievements and everything to the success of the tributes paid to them.

7. What I did not yet know so intensely was the hatred of the white American for the black, a hatred so deep that I wonder if every white man in this country, when he plants a tree, doesn't see Negroes hanging from its branches.

8. I give the name

Violence

to a boldness lying idle and in love with danger.

9. I couldn't change the world on my own, I could only pervert it: that is what I attempted by a corruption of language - that is to say from within this French language that appears so noble.

10. I don't have readers, only thousands of voyeurs.

French poems in honour of Jean Genet & Antonin Artaud

It is fascinating to compare and contrast the careers of Oscar Wilde and Jean Genet.

Had Wilde lived in France he would have become a member of the French Academy, like Gide.

Had Genet lived in England he would never have been heard of.

Nor would Artaud.

Because they lived in the century of mass-production, mass-communication and mass-terror, their reactions were not mealy-mouthed. Neither could have been a Holy Fool as they might have been in an earlier time - for surely thousands of Holy Fools have lived in Europe, blessed by obscurity and oblivion.